Vocabulary: Noun Things

manor

armada

- What Will Replace The Internet?

- By Vinton Cerf.

http://www.time.com/time/magazine/article/0,9171,997263,00.html

ungulates

varicose

insignias

mandible

frontispiece

hotcake

bric-a-brac

cowcatcher

cataract

palimpsest

- Deleting History: Why Governments Demand Google Censor the Truth

- By Lauren Weinstein.

- http://lauren.vortex.com/archive/000826.html

causeway

reservoirs

duffel

lanyard

halberd

dirndl

chronograph

A chronograph is a specific type of watch that is used as a stopwatch combined with a display watch. A basic chronograph has an independent sweep second hand; it can be started, stopped, and returned to zero by successive pressure on the stem. Nicolas Mathieu Rieussec invented the chronograph in 1821. Rieussec was awarded the original patent for his chronograph in 1822.

There are many modern day uses for the chronograph, but the original use for this device, and also the reason it was invented, was to please King Louis XVIII in 1821. The King greatly enjoyed watching horse races, but wanted to know exactly how long each race lasted, so Nicolas Rieussec was hired to invent a contraption that would do the job. As a result, he created the first ever commercialized chronograph.

chronometer

A marine chronometer is a clock that is precise and accurate enough to be used as a portable time standard; it can therefore be used to determine longitude by means of celestial navigation. When first developed in the 18th century it was a major technical achievement, as accurate knowledge of the time over a long sea voyage is necessary for navigation, lacking electronic or communications aids. The first true chronometer was the life work of one man, John Harrison, spanning 31 years of persistent experimentation and test that revolutionized naval (and later aerial) navigation enabling the Age of Discovery and Colonialism to accelerate.

The term chronometer (apparently coined in 1714 by Jeremy Thacker, an early competitor for the prize set by the Longitude Act in the same year) is used more recently to describe wristwatches tested and certified to meet certain precision standards. Timepieces made in Switzerland may only display the word ‘chronometer’ if certified by the COSC (Official Swiss Chronometer Testing Institute).

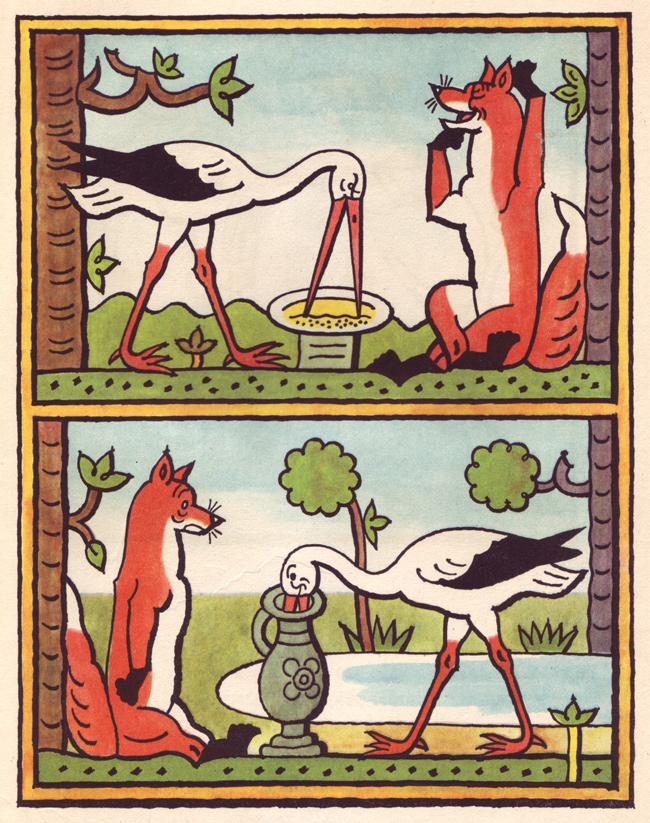

stork

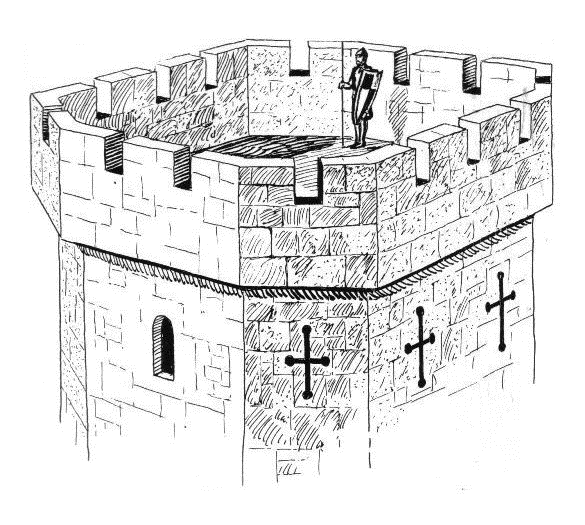

battlement

J. K. Rowling says she visualises Hogwarts, in its entirety, to be: «A huge, rambling, quite scary-looking castle, with a jumble of towers and battlements. Like the Weasley's house, it isn't a building that Muggles [non-magical humans] could build, because it is supported by magic.»

citadel

When private illusion clashes with social reality, the former should, in the normal course, make way. It does not always happen thus in contemporary India though. Consider, for instance, the case of the dowager queen of Rae Bareilly. She is just that, the dowager queen of Rae Bareilly. She is however under the illusion that the whole of India is her demesne by virtue of dynastic rights. The social reality, which of course includes political reality, is altogether different. Forget about India, she and her party cannot lay claim even over Uttar Pradesh, the erstwhile citadel of the Nehru-Gandhis; the Congress is, in electoral terms, only the fifth party in that state. This reality does not faze Sonia Gandhi because of the curious coalition known as the United Progressive Alliance. The alliance enables the Congress to preside over the government at the Centre. It also enabled Sonia Gandhi to be chairman of the National Advisory Council, so-called, thereby misleading the lady into believing that India exclusively belongs to her.

The private illusion helps to create an ambience of quintessential medieval days when only kings and emperors mattered, nobody else did. Given the make-believe of the Middle Ages, feudal skirmishes enjoy the prerogative of occupying centrestage. The Nehru-Gandhi dynasty was once inseparable from the Bachchan clan. The time machine is however at work; the two clans have since travelled far from each other, and are now sworn enemies. Sonia Gandhi and her cronies want to see the ruination of the Bachchans.

- CLANS DO NOT MAKE INDIA - It is a hard choice between feudalism and sectarianism

- By Cutting Corners Ashok Mitra.

- http://www.telegraphindia.com/1060414/asp/opinion/story_6092055.asp

bastion

- Why Microsoft Can't Get Rid Of IE6 Yet

- By Daniel Bailey.

http://www.conceivablytech.com/8304/business/why-microsoft-cant-get-rid-of-ie6-yet

bile

- How the internet created an age of rage

- By Tim Adams.

- http://www.guardian.co.uk/technology/2011/jul/24/internet-anonymity-trolling-tim-adams

backhoe

sinew

pachyderm