Chinese measure words 量词 (collective nouns)

Chinese measure words (collective nouns)

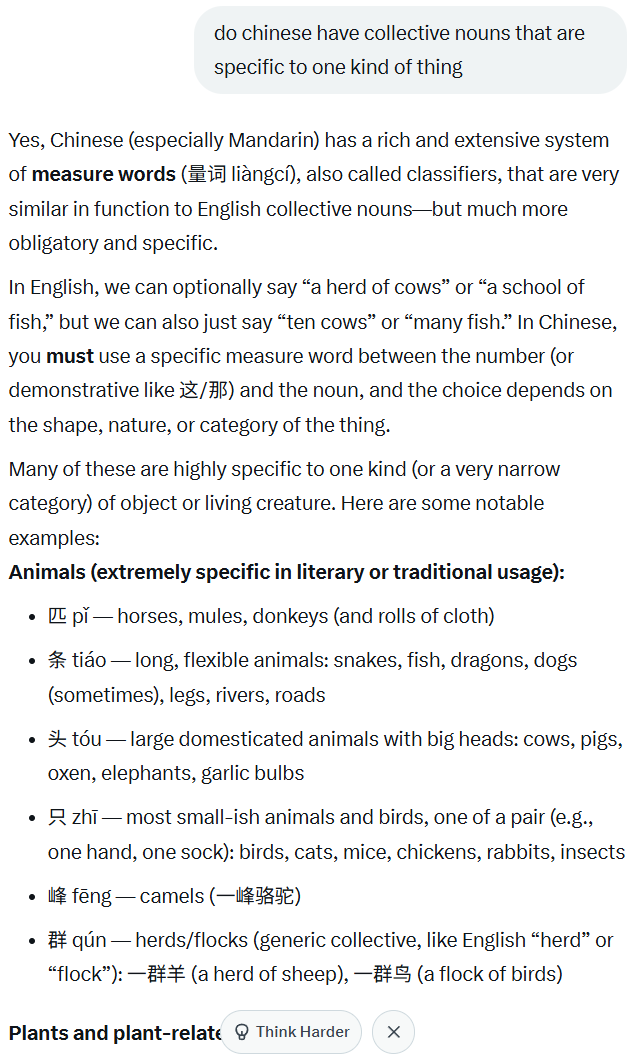

- do chinese have collective nouns that are specific to one kind of thing.

- what's the history of chinese measure words.

- https://x.com/i/grok/share/aVE7ztQigO0y0IJ0Z4LpxqKpZ

- Almost no obligatory measure words.

- Numbers could directly modify nouns, just like in English (“three horse”, “five people”).

- A few nouns were already used as “proto-classifiers” when needed for clarity, especially for animals and objects:

- 匹 pǐ for horses (already appears in oracle bone inscriptions ~1200 BCE)

- 乘 shèng for chariots

- 头 tóu for cattle (rarely)

- These were optional and still felt like regular nouns (“three horses” = 三馬 or 三匹馬).

- The system starts to grow rapidly.

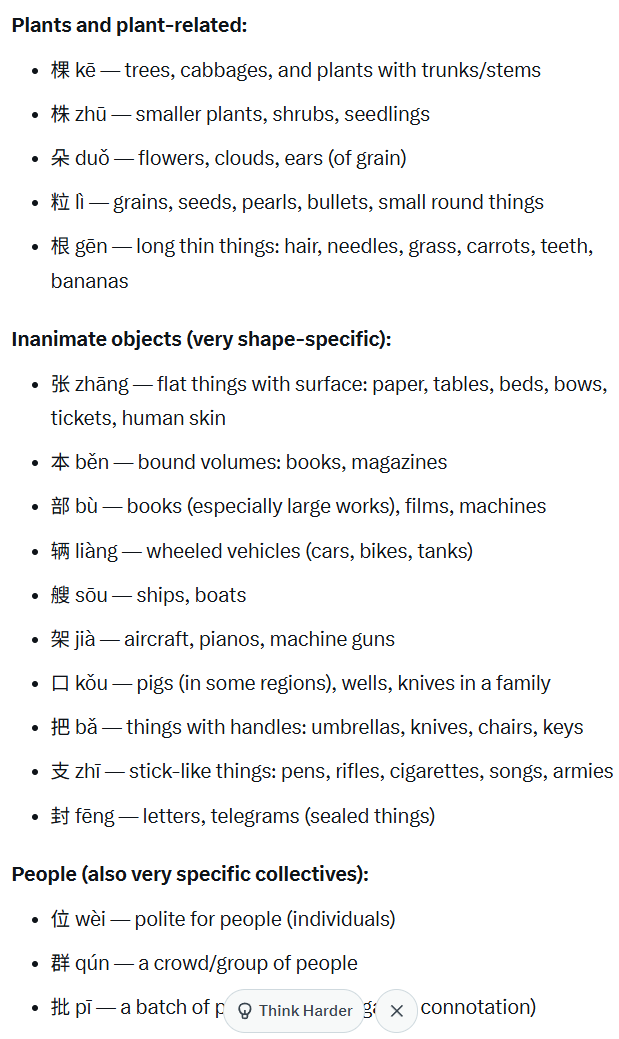

- More and more nouns are “bleached” of their original meaning and turn into pure classifiers. Examples:

- 口 kǒu “mouth” → classifier for people and pigs (because you feed them through the mouth)

- 首 shǒu “head” → for songs and poems

- 張 zhāng “to stretch” → for things that are stretched out (paper, bows, beds)

- 枚 méi (originally a small branch or coin) → general classifier for small roundish objects

- By the end of this period, using a classifier after a numeral or demonstrative (这/那) becomes very common, though still not 100 % mandatory in all texts.

- Classifiers become virtually obligatory in spoken and most written language.

- The famous “general classifier” 个 gè (originally “bamboo stalk”) rises dramatically in the Tang–Song period and starts to replace many more specific classifiers in everyday speech (especially in northern China). This is why modern Mandarin uses 个 so widely.

- Literary language keeps hundreds of specific classifiers; colloquial language starts simplifying.

- Northern Mandarin (the basis of modern Standard Chinese) continues to generalize 个 gè so that it can be used with almost anything, especially people, abstract concepts, and when you forget the “correct” one.

- Southern Chinese languages (Cantonese, Minnan, Wu, Hakka, Gan, etc.) keep a much richer and stricter classifier system with far less overuse of the general classifier (Cantonese still has 條, 隻, 粒, 張, etc., used much more rigorously than Mandarin).

- 1950s–1980s: Language reformers try (and fail) to reduce the number of classifiers or make 个 the only one.

- Standard written and spoken Mandarin settles on about 50–80 commonly used classifiers, with 个 being by far the most frequent (covers ~50–70 % of all uses in ordinary speech).

- Literary, poetic, or technical registers still demand the precise traditional one (e.g., you must say 一匹马, not 一个马 for “one horse” in most formal writing).

- Analytic language: lost almost all inflectional endings, so word order and particles/classifiers became crucial for clarity.

- Monosyllabic tendency: when most words are one syllable, adding a classifier prevents ambiguity (三本书 vs just 三书).

- Cultural habit of categorizing the world by shape and kind rather than by plural morphology.

Very Brief History of Chinese Measure Words (量词 liàngcí)

1. Old Chinese (before ~200 BCE)

2. Han Dynasty and Six Dynasties (200 BCE – 600 CE)

3. Tang and Song Dynasties (618–1279 CE): The modern system takes shape

4. Yuan, Ming, Qing (13th–19th centuries)

5. 20th century – Modern Mandarin

Quick timeline summary

Period State of classifiers Pre-Qin (~1200–200 BCE) Only a handful, optional (匹, 乘, etc.) Han–Six Dynasties Rapid growth; many nouns → classifiers Tang–Song Almost obligatory; 个 gè begins its takeover Yuan–Qing Northern vernacular heavily favors 个; south keeps variety 20th–21st century Modern Mandarin: ~70 common ones, but 个 dominates speech Why did Chinese develop so many?

In short, what started as a handful of optional nouns for animals and vehicles in the Bronze Age turned into one of the most elaborate and obligatory classifier systems in the world’s languages, and it reached its basically modern form by the Tang dynasty about 1,300 years ago.